GENK’S ECONOMIC SHIFT: From mining coal to mining data – TRADERS Autumn School – Data mining working table

As part of the second international Autumn School of TRADERS, themed “On the role of participatory art and design in the reconfiguration of work (in Genk)”, Saba Golchehr hosted a workshop on data mining titled ‘Genk’s economic shift: From mining coal to mining data‘.

In order to familiarise the participants of this working table to the context and the topic of the workshop we started our session with two introductions. The first introduction was given by Liesbeth Huybrechts, in which she explained our case study: the Kolenspoor project. Following this, I gave an introduction on the theme of this working table.

First, the participants were asked to share their conceptions of, and experience with, Big Data, data mining and algorithms. Following up on their contribution, I introduced my main research aim and my approach to data mining. Here, I emphasised on the difference between traditional data analysis and data mining in the ‘Big Data era’, and elaborated on where the essence of the data-driven approach lies in my research and therefore also in the workshop. This introduction opened up some interesting paths for the workshop for us to discuss.

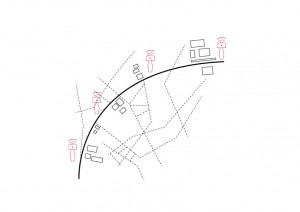

One of the outcomes of this discussion was the idea of crowdsourcing data collection on the Kolenspoor project. We talked about how we could approach this systematically, and I explained that in a ‘Big Data approach’ metadata is of equal importance as the data aimed at collecting. As a result of this discussion we explored what data we could gather when taking photos of the site, and decided to focus on geo-location to be able to automatically map photos (data) that we would collect. After altering some camera settings in our smartphones to capture geo-data for photos, we went outside to visit one of the sites along the Kolenspoor track. Here we all took pictures and uploaded these to our shared database.

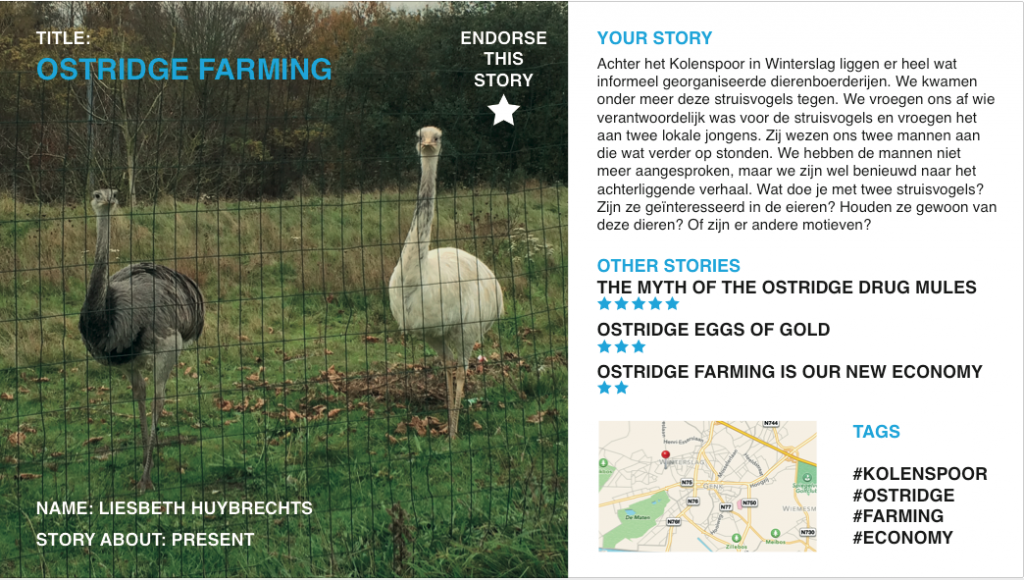

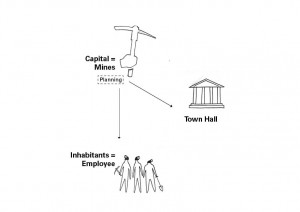

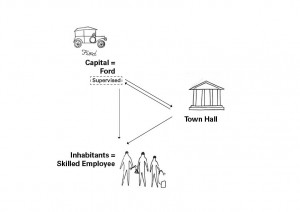

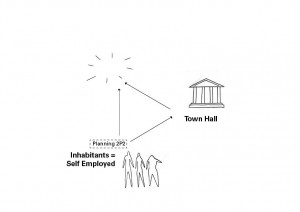

During our visit to the site we noticed a lot of informal economic activity along Kolenspoor track. There were small animal farming activities (ostriches, chicken, goats) and small-sized food agriculture, but there also seemed to be some (illegal) trade in cars and building materials. Liesbeth also informed us that the cafeteria located along the track wasn’t a formal enterprise, but that it was nevertheless tolerated by the municipality, because they recognise the social value of such establishments. After our site visit we reflected on these activities and started discussing about a model in which these informal economic activities would be the foundation of a new economic model for Genk. We reflected on how the town has always been dominated by a triangular structure of labour (capital), council (state) and employees (public), in which labour was provided by large monopolies (the coal mines and later the Ford factory).

This pillar in Genk’s economic structure has now for a great part collapsed due to the closing of the Ford factory. In order to move towards a more resilient economic model, where the town does not have to rely on large enterprises to provide labour in the future, we proposed an alternative system in which the main economic driver is shaped by self-employment. In our conceptual model we proposed to achieve this by creating more openness in the local informal economic activities and have the town recognise them as formal labour.

The first step in this process consists of creating visibility of these activities. We proposed a method to collect data on this in an opaque way, where inhabitants can share their story on a digital platform. This platform would function as a peer-to-peer system in which the different stories, whether fact or fiction, would be collected and would provide an insight into the spatial and the social dimension of the sites. In the background of this platform these added stories would be saved in a database that can function as a source for data analysis in a later stage, by providing metadata (next to the qualitative data, i.e. the stories) that can be used to explore other issues that might become relevant in the future. In order to avoid excluding the non-digital population, we proposed to also place physical artefacts along the Kolenspoor tracks where people can record their stories in situ.

We then developed a conceptual economic context to embed this system in, where we emphasise on the reciprocal nature of data collection; inhabitants that would provide their data (i.e. stories) would get something in exchange. This exchange could take place through credits provided by local entrepreneurs in the area, which would be handed to the data contributors by the town (the town would be monitoring the contributed data and recognise the local enterprises as formal once they take part in this system). The data contributors would receive credits and would be able to hand in these credits at the local enterprises in exchange for a service or product provided by this enterprise.

Our aim for this workshop was to develop a conceptual scenario in which data collection would be crowdsourced, and where the value of people’s data would be recognised. By proposing a system of exchange we aimed to support and strengthen local economic activity around the Kolenspoor track.