‘Design, Social Media and Technology to Foster Civic Self-Organisation’ Conference

Over the last two decades Europe has been witnessing an increased demand for participation when it comes to decision-making processes. Both citizens, demanding more direct forms of democracy, and governments, e.g the idea of ‘Big Society’ in the UK and the ‘Participation Society’ in the Netherlands, plea for civic self-organisation. The ‘Design, Social Media and Technology to Foster Civic Self Organisation’ conference, hosted by the University of Hasselt in collaboration with TRADERS, is organised around the idea that design and digital technologies play a crucial role in this development.

The conference is structured by the following tracks:

1. How can design, social media and technology encourage and empower citizens to take part in and/ or start up civic self-organisation practices?

2. How can design, social media and technology sustain civic self-organisation practices over longer time periods, and within a diversity of socio-economic contexts?

3. How can the impact of design, social media and technology on civic self-organisation practices be documented and evaluated?

Saba Golchehr (Royal College of Art) and Naomi Bueno de Mesquita (Design Academy Eindhoven) see data-mining and digital mapping technologies as potentially valuable approaches for durable participation. In a jointly written paper they focus on the second track; how design, social media and technology can sustain civic self-organisation practices over longer time periods, and within a diversity of socio-economic contexts. The abstract for this paper can be read here.

TECHNOLOGY AND DESIGN FOR CIVIC ENGAGEMENT;

Digital technologies in art and design practice for durable participation in public spaces

keywords: data-mining, digital mapping technologies, durable participation, civic engagement, community building

[Problem statement]

A growing number of spatial projects have started using digital technologies such as data mining and mapping for community engagement and civic self-organisation. In our examination of these projects we have noticed that a large number of them are focused on environmental issues. These projects are often initiated by professionals (such as designers and artists), which begin from their own interests or preconceptions about the needs of a community. Although they might be relevant for environmental or societal awareness, the projects rarely become rooted in the community where they are implemented. There is hardly ever a follow-up of the social intervention, and they rarely trigger any kind of civic self-organisation.

An example of such a project is Feral Robotics Public Authoring, a collaboration between artists’ studio Proboscis and artist Natalie Jeremijenko, that took place in London Fields park in Hackney, London in 2006. This project enables people to explore their local environments with electronic sensors that they attach to DIY modifications of toy dogs or DIY built robots that detect air quality, noise and light pollution, and are visualised through online tools. The combination of cheap electronics (such as toy robots) with online tools strives to give people the feeling that they can learn about their environment in a fun and tactile way, while collecting evidence (through mapping) that instigates action. This project was introduced in robot-building workshops and mapping workshops that took place during traditional community events (village fetes and local festivals etc). The studio imagined a growing network of hobbyist data collectors, developing over the years after they initiated the project, who would start mapping their own environment and take action to initiate change (Lane et al., 2006). However, the project never resulted in follow-up civic self-organized projects or any other long-term effect, such as the community organising their own workshops to build tools to measure air quality, or to compare the collected data with ‘official’ government data. This absence re-occurs in many community-related digital mapping and data mining projects. A clear symptom of this phenomenon is the large amount of projects of which the hyperlink is inactive a couple of years after the project has finished. In fact, we found very few community-driven projects that used data mining and digital mapping and embedded these in a long-term civic engagement approach. So one might question how sustainable these projects are. Why do they fail to initiate follow-up action or sustain civic self-organisation? Could this be caused by the projects’ design, or does it depend on who initiates the project and to what ends? Equally, is the absence of an ‘afterlife’ to the project – civic self-organisation – the initiators’ responsibility?

In the Feral Robotics example, the professionals (Proboscis) imposed their idea of ‘public authoring’ as something that would empower the community, without conducting any prior investigation into the community’s interests or needs. They also neglected to investigate whether the way in which the project was conducted was appropriate for that specific community. Their project design was based on workshops in which the professionals taught and guided the participants on making the robots and going out to collect data. We notice that many similar projects are introduced by workshops, but one might question if the workshop culture isn’t much more the language of the designer and whether it is an appropriate project design for the community in which it is presented. In the present culture of intervention, the most committed artists and designers try to become educators (or in some cases social workers), and this is something our paper will challenge.

To do this, we will focus on the notion of durability and the designers’ responsibility. The design of a project should take into account what happens after the designers leave and who benefits from the work (what designers ask from their participants and what they give in return). Our paper will therefore present the potential of data-mining and digital mapping technologies to foster civic self-organisation, and enhance long-term community participation while allowing artists and designers to remain artists and designers.

[Aim]

Our aims are:

- to investigate whether this recurring lack of community embeddedness is due to the ways in which such projects are initiated and designed;

- to investigate the extent to which the artist/designer can or should take responsibility for that embeddedness.

- to investigate how artists and designers can use digital technologies for increasing community engagement in projects.

By analysing case studies we want to explore how data mining and mapping is used by, with and/or for a community. Furthermore, we want to explore the following questions about designers’ methods: In which stages do they use physical tools, and in which stages digital ones? What do they aim to achieve with these tools? And are these tools transferable? How do the project initiators approach potential participants? How does the community/potential participants access information provided by the initiators? How do the initiators engage in the local community? And does the community continue the project after the initiators move on? What are the long-term effects of the project?

[Method & approach]

Our research uses two methods: a literature review and an analysis of actual cases of community projects following the Grounded Theory methodology. Grounded Theory challenges the traditional deductive approach in social sciences in which one first forms a hypothesis based on theory and then collects data to support or reject this hypothesis. In this approach the emphasis of the research often lies on verifying the theory (Kelle, 2005). In the Grounded Theory approach however, one starts by collecting and analysing data, in order to discover theory from that data. This way theory can emerge from the data. We will follow this methodology for our exploration of empirical data from the case studies. From this analysis several themes emerge, which we will take apart and elaborate on through theory.

We will select case studies with a varying socio-economic context to analyze in what way these contexts plays a role in the designers’ choice of tools and form of communication with the participants. Within the case studies we are particularly interested in the digital tools used in spatial practice, that allow a community to appropriate a project. Therefore we will explore how digital technologies can facilitate long-term participatory public space projects (on a neighbourhood scale) and how the initiators and participants view their projects in the long term, after the designers leave.

[Case studies]

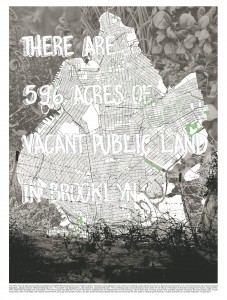

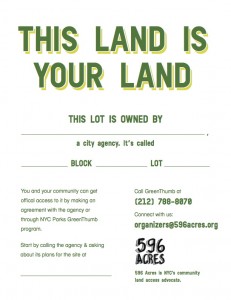

596 Acres is a non-profit organisation that uses both digital technologies and physical interventions to initiate community projects through social interventions. A team of design and information technology professionals aim to help citizens transform vacant public land in the city of New York into community resources (“596 Acres Recap”, 2012). 596 Acres began by analysing open data on vacant land provided by the city. It then focused on the development of online tools that transformed city data into ‘readable’ information for citizens by mapping all publicly owned vacant pieces of land in the city of New York (fig.1). They then designed a physical intervention: Posters were put up (fig. 2) on the fences surrounding the vacant lots – containing provocative texts (e.g. ‘This Land Is Your Land’), basic information about the city agency owning the lot, and their contact number. These posters, in combination with digital information (numbers, figures and maps on the 596 Acres website) managed to trigger local neighbourhood inhabitants to contact the NGO and take action. Over the last three years they helped twenty-two groups get official permission to access the lots, and supported 143 local campaigns to transform vacant lots into gardens, farms and playgrounds (Segal, 2014). 596 Acres acknowledge the importance of making information available to the community ‘on the ground’ by using both physical (offline) as well as digital (online) methods of showing the municipal information. The next step in 596 Acres’ practice is guiding interested participants in the process of appropriation. For instance, they provide education to locals about how to participate in decision-making processes by the city government that affect their neighbourhood; they assist communities with legal support on land use issues; they work with the community after they get access to the land in order to build a durable local governance, and they argue for municipal agencies to allow for more community participation concerning public resources. Their practice clearly focuses on a long process of counselling and cooperation in order to create a civic self-organisation around these publicly owned lots. Furthermore, 596 Acres uses social media to support and grow a larger community around the projects and to maintain a network among communities in order to share knowledge and ties with decision-makers.

We are conscious of the fact that in these kind of projects the role of the designer can easily transform into one of a social worker. With our research we want to be more aware of this emerging trend and explore the opportunities for designers to re-engage in design. We want to explore this by posing three possible roles for a designer within the context of triggering civic self-organising projects with the use of data mining and mapping technologies: (1) designing a platform, (2) designing a project, and/or (3) designing for a client (the client being the community). In the example of 596 Acres, the project was not imposed on a community, instead the posters waited for participants to contact the NGO and the digital means were easily appropriated by the community. This project shows that there can be an on-going community engagement, even when a project is initiated by professionals. By understanding the needs of the community in this specific socio-economical context (there is a lot of competition for land in Brooklyn and communities benefit economically from growing their own produce), the project was appreciated and appropriated by the community.The participants contacted the organisation in order to gain access to the land and use it for their desired purposes. This example demonstrates that people are much more inclined to participate and to appropriate a tool or project if they have some sort of personal gain, which is often the only form of motivation for collective engagement, or if they can achieve something that they wouldn’t be able to achieve alone (Petrescu, 2007; Sennett, 2012).

By looking at actual cases we want to explore how digital tools (such as data mining and mapping) can be employed to sustain civic self-organisation/community projects. Finally, this research will form input for our ongoing PhD research by exploring how we can incorporate or improve these tools in our own case studies.

[References]

596 Acres 2011-2012 Recap. 2012. Available here. [Accessed: 17 Oct 2014].

Glaser, B.G. 1978. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley: Sociology Press.

Kelle, U. 2005. ’ “Emergence” vs. “Forcing” of Empirical Data? A Crucial Problem of “Grounded Theory” Reconsidered’. In: Forum Qualitative Research. Vol. 6. No. 2. Art. 27. Available here. [Accessed: 13 May 2014].

Lane, G. et al. 2006. Public Authoring & Feral Robotics. In: Proboscis. Cultural Snapshot Number Eleven. Available here. [Accessed: 8 Nov 2014].

Petrescu, D. 2007. ‘How to make a community as well as the space for it’. In: Re-public: Reimagining Democracy. Available here. [Accessed: 10 Oct 2014].

Segal, P. 2014. OpenGov Voices: How 596 Acres is opening up vacant lots data. Sunlight Foundation [web log]. Available here. [Accessed: 13 Nov 2014].

Sennett, R. 2012. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures, and Politics of Cooperation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[Images]