Introducing Digital Methods for On-going Community Participation

For the conference ‘Design, Social Media and Technology to Foster Civic Self-Organisation’, Saba Golchehr (Royal College of Art) and Naomi Bueno de Mesquita (Design Academy Eindhoven) wrote a paper in which they introduce digital methods (data-mining and digital mapping) as potentially valuable approaches for designers to create more sustainable interventions.

The conference is structured by the following tracks:

1. How can design, social media and technology encourage and empower citizens to take part in and/ or start up civic self-organisation practices?

2. How can design, social media and technology sustain civic self-organisation practices over longer time periods, and within a diversity of socio-economic contexts?

3. How can the impact of design, social media and technology on civic self-organisation practices be documented and evaluated?In the paper they focus on the second track; how design, social media and technology can sustain civic self-organisation practices over longer time periods, and within a diversity of socio-economic contexts. The conference is hosted by the University of Hasselt in collaboration with TRADERS. The paper can be read here.

INTRODUCING DIGITAL METHODS FOR ON-GOING COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

How social data can help inform designers to develop sustainable design interventions

Keywords: digital methods, geolocated social data, on-going participation

[Abstract]

A growing number of designers adopt digital methods when working in a public space context. While many of them aim to trigger civic self-organisation through their projects, they either fail to sustain civic participation after they leave, or they remain engaged in a project remarkably long to safeguard on-going participation (often turning into social workers). This paper argues that two key features should be addressed in design-projects that aim for on-going community participation: acknowledging existing communities and understanding communities’ interests. We explain how digital methods can be used to explore these features by introducing two approaches. The first approach sets out from established (virtual) communities and explores where those communities are located. The second approach starts from an established location for a planned intervention and explores the communities that are active there. These approaches aim to inform designers in (co-)designing public space interventions that allow communities to identify with, appropriate and maintain the design, in turn allowing designers to leave the scene without jeopardising the sustainability of a project. The paper concludes that contemporary technological advances can play a great role in contributing to new approaches for safeguarding the longevity of users’ engagement in a physical design.

[Introduction: digital methods for design interventions]

Digital methods, such as data mining and mapping, are increasingly used in spatial projects with the aim of enhancing community engagement or civic self-organisation. In our observation, a large number of these projects are initiated by professional artists or designers who set up projects from their own interests or preconceived ideas about the needs of a community. Although they might be relevant for raising environmental or societal awareness, the projects often don’t become rooted in the community where they are implemented. The design interventions are hardly ever sustained and they rarely trigger any kind of civic self-organisation.

In this paper we shed light on the shortcomings of art and design practices that adapt digital methods, while aiming to develop projects that enable on-going participation. Focusing on communities’ appropriation of the design project and of public space, two examples are studied that form the foundation of the two suggested approaches. Following the deconstruction of these examples, the argumentation of the current problematic and the articulation of a hypothesis, this paper introduces other examples, from both art and design practices and other fields, that illustrate how digital methods can be of value within these two approaches. It should be mentioned that the problem of the digital divide is not elaborated on in this paper. For this reason all projects are exclusive to the extent that they don’t consider people who are less active on social media or other virtual platforms. Instead, the focus purely lies on the potential benefits that the study of social data can have for design professionals working within the context of public space.

[Digital methods for public authoring]

The first project we will analyse is a collaboration between artists’ studio Proboscis and artist Natalie Jeremijenko, named Feral Robotics Public Authoring, that took place in London Fields park in Hackney, London in 2006. This project enabled people to explore their local environments with electronic sensors that they attached to DIY modifications of toy dogs or DIY built robots that detected air quality, noise and light pollution, and of which the data was visualised through online tools. The combination of cheap electronics (such as toy robots) with online tools was aimed at giving people the feeling that they could learn about their environment in a fun and tactile way, while collecting evidence (through mapping) that, in turn, would instigate action. This project was introduced in robot-building and mapping workshops that took place during traditional community events (village fetes and local festivals), which therefore attracted a lot of local participants. The studio imagined a growing network of hobbyist data collectors, developing over the years after they initiated the project, who would start mapping their own environment and take action to instigate change (Lane et al., 2006). The project, however, never resulted in on-going civic self-organisation nor did it have any other long-term effect, such as the community organising their own workshops to build tools to measure air quality, or to compare the collected data with ‘official’ governmental data. Failing in achieving sustained action seems to re-occur in many community-related projects that utilise digital methods, of which a clear symptom can be seen in the large amount of projects where the hyperlink is inactive a couple of years after the project has finished (for example: koppelkiek.nl and citizensensing.org). In fact, we found very few community-driven projects that have adapted and embedded digital methods, such as data mining and mapping, in a long-term citizen engaging approach. This raises questions as to how sustainable these projects can actually be. Why do they fail to initiate on-going civic action or sustained civic self-organisation? Could this be caused by the projects’ design, or is it dependent on who initiates the project and to what end? In the next section we will look at another example that uses digital methods, and that aims for long-term civic empowerment, but adopts a different approach.

[Digital methods to trigger community appropriation]

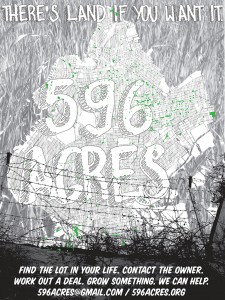

The second example that deals with community empowerment and sustained local action is the work of non-profit organisation 596 Acres. Here, a team of design, law and information technology professionals aims to help citizens transform vacant public land in the city of New York into community resources (596 Acres Recap, 2012). 596 Acres began by analysing open data on vacant land provided by the city, after which they developed online tools that transformed city data into ‘readable’ information for citizens. This was done by mapping all publicly owned, vacant pieces of land in the city of New York (fig.1) and by designing a physical intervention; posters were put up (fig. 2) on the fences surrounding the vacant lots containing provocative texts (e.g. ‘This Land Is Your Land’), basic information about the city agency owning the lot and their contact number. These posters, in combination with digital information (numbers, figures and maps on the 596 Acres website), triggered local neighbourhood inhabitants to contact the organisation or the local council and take action.

Fig 1 – 596 acres of vacant land in Brooklyn (left). Fig 2 – Poster as physical intervention (right) (596acres.org)

Over the last three years they helped twenty-two groups obtain official permission to access the lots and supported 143 local campaigns to transform vacant lots into gardens, farms and playgrounds (Segal, 2014). 596 Acres acknowledge the importance of making information available to the community ‘on the ground’ by using both physical (offline) as well as digital (online) tools for showing the municipal information. The next step in 596 Acres’ practice is guiding interested participants in the process of appropriation. For instance, they provide education to locals about how to participate in decision-making processes by the city government that affect their neighbourhood; they assist communities with legal support on land use issues; they work with the community after they get access to the land in order to build a durable local governance; and they argue for municipal agencies to allow more community participation concerning public resources. Furthermore, 596 Acres uses social media to support and grow a larger community around the projects and to maintain a network among communities in order to share knowledge and ties with decision-makers. Their practice clearly focuses on a long process of counselling and cooperation in order to create a civic self-organisation around these publicly owned lots. This paper therefore raises another question: Such projects are centred around creating, maintaining and educating communities, but is this the direction that designers should be heading to be able to prolong the life of a design intervention?

[Hypothesis]

In the Feral Robotics example, the professionals (Proboscis) imposed their idea of ‘public authoring’ as something that would empower the community. The project was initiated from the interests of the professionals and artist as an experiment to explore a site from an “environmental, personal and community point of view” (socialtapestries.net). In their documentation of this project we were unable to find any traces of a prior investigation into the community’s interests or needs for such an intervention. Their project design was based on workshops in which the professionals taught and guided participants on making the robots and going out to collect data. By hosting this workshop at a traditional local event they were able to reach a large number of community members and by doing so, they were able to embed their actions within an existing community. The project was therefore successful in terms of engagement and participation during the workshop, but failed to turn this ephemeral intervention into a continuous community-driven, sustained neighbourhood project.

In the 596 Acres example, the project was not imposed on a community; instead the strategically placed posters awaited participants to contact the NGO. This project shows that there can be an on-going community engagement, even when a project is initiated by professionals. By understanding the needs of the community in this specific socio-economical context (there is a lot of competition for land in Brooklyn and communities benefit economically from growing their own produce), the project was appreciated and appropriated by the community. Although this project was successful in terms of the longevity of community participation, it also illustrates that we need to be aware of the fact that in these kinds of projects the role of the designer can easily transform into one of a social worker. This paper counters this emerging trend and explores opportunities for designers to re-engage in design. The 596 Acres project mostly exists of professionals investing their time to create a community that can sustain the intervention, but is that a role designers should take on? This paper argues that in order to avoid becoming social workers, designers should not aim to create new communities around their projects, but instead investigate existing communities, which they can enter and, after developing embedded projects, can exit, while the community appropriates and prolongs the life of the project.

Summarising the lessons learned from the two examples, this paper puts forward the following hypothesis:

Design interventions can be on-going and sustained by a community without the continued involvement of a designer if at least both:

1. The design intervention is based on the interest of users/a community (in terms of program: e.g. allotments); and

2. The design intervention is planned within an existing community or social network.

Design projects that use digital methods while achieving sustained community participation are scarce. We argue that digital methods can offer new opportunities for lasting impact by designers and therefore suggest two approaches for to studying digital social data prior to designing an intervention. These two approaches are aimed at uncovering existing communities, their interests (in terms of the program for the intervention) and potential locations for the design intervention. With these approaches we explore how digital methods can be used to achieve both points of the hypothesis which, we argue, would result in projects with more potential of being sustained by communities, while enabling designers to re-engage in design.

The first approach starts from a known community and explores potential locations and interests of this community for the design intervention. The second approach starts from an established location for the intervention and explores what communities exist on that location and what interests they have. The case studies that are described in the following sections are categorised by these two approaches.

[FROM COMMUNITY TO LOCATION]

Geocachers; virtual communities (re)discovering physical places

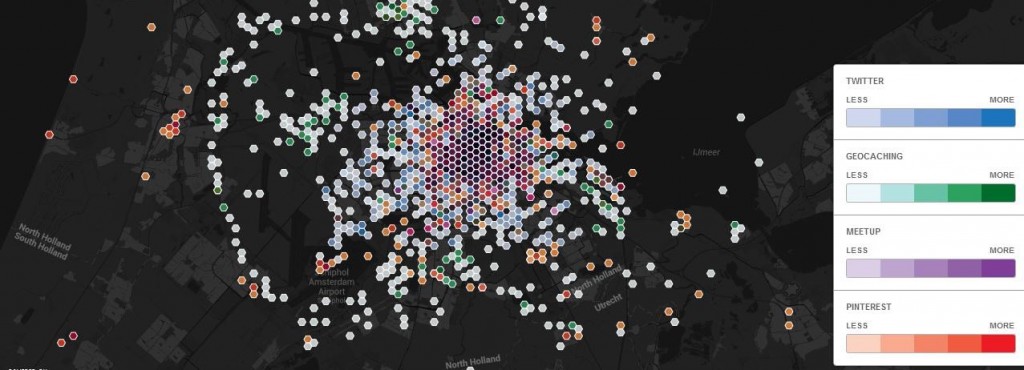

The first example of exploring digital methods is a study (performed at the Digital Methods summer school at the University of Amsterdam in June 2014) of mining and mapping social data produced by different virtually constructed communities. This study explored different virtual communities (on social media and other virtual platforms) and their relation with physical places in the city. The data for this study was produced and published by Amsterdam based users, and subtracted from the platforms Twitter, Meetup, Pinterest and Geocaching. Through applying digital methods the geolocated embedded links, tags, threads and pin-boards were mapped (fig. 3), demonstrating the places in the city the different virtual communities talk about or ‘hang out’ at. For the Twitter dataset the keyword ‘Amsterdam’ was retrieved over a 10-day period (June 13th-22nd 2014). As for the datasets of Pinterest, the term ‘Amsterdam’ was searched for in ‘place’ boards. The dataset of Meetup gave 489 events over a four-month period in this city. And for Geocaching all the existing caches (718, of which 39 temporarily inactive) placed in Amsterdam were collected.

Fig 3 – Virtual communities formed on Twitter, Geocaching, Meetup and Pinterest in Amsterdam. This map forms part of the Digital Methods Summer School at the University of Amsterdam in June 2014 (Credits: Michele Mauri – participant of the summer school)

The map reveals that most platforms (Twitter, Meetup, Pinterest) are located in or around the centre; Pinterest clearly represents the boutique view of Amsterdam (outlining the nine-streets, Haarlemmerdijk and Haarelemmerstraat), while the virtually constructed communities of Meetup consist of people with a common interest (for instance in technology, fitness or fine arts) who temporarily gather in bars, mostly around the square of Nieuwmarkt. Of these four platforms, only the users of Geocaching are likely to engage with places that are harder to get to, e.g. the city’s periphery. Geocaching is therefore the most widely spread community in Amsterdam in terms of physical range, which can be explained by the nature of the game and purpose of the platform (elaborated in the next paragraph). From this study we also found that the communities on Meetup and Pinterest focus primarily on the strengthening of a user’s personal identity linked to commercial places, therefore mostly informing us about users as consumers of places. The Geocaching community, on the other hand, is keen on exploring a wider range of locations that are not limited by commercial use, or the city’s borders (fig. 4). Within the context of long-term user engagement and appropriation (in terms of taking ownership) of physical places, the Geocaching community offers a wider range of opportunities for designers to work with in terms of program and location for interventions. Therefore, we will study the (virtual) nature of this community and their relation to the physical dimension more closely in the next paragraphs.

Fig 4 – Photos from the geocaching communities’ website. The map demonstrates the Geocaches that are located in and around Amsterdam. The images demonstrate places where geocaches navigate through and how natural sites and the periphery of cities are part of the game-board (geocaching.nl).

Fig 4 – Photos from the geocaching communities’ website. The map demonstrates the Geocaches that are located in and around Amsterdam. The images demonstrate places where geocaches navigate through and how natural sites and the periphery of cities are part of the game-board (geocaching.nl).

Geocaching is a treasure hunt game that emerged in the year 2000 after the Global Positioning System (GPS), initially developed for and used by the U.S. army exclusively, was made available to the public. Geocaching exists of a game where participants hide a ‘cache’ somewhere in public space and provide clues to other players on its location. By following these clues the participants are ‘navigated’ through the city, or through a natural site. After hiding a treasure, the person who placed the cache announces the location to the other Geocachers through the Internet. Other Geocachers can exchange or add items in the cache upon discovering the treasure, after which they write about the cache in the log via the website. The exchange and logging activities illustrate how actions in Geocaching take place within, and alter between, the physical and the virtual realm.

The following map (fig. 5) demonstrates all the caches at the time of data collection that are placed in Amsterdam. The map visualises the amount of logged visits to a cache, which can be read in the size of the dots. Furthermore, it demonstrates the comments-per-visits ratio: the most intense red-coloured dots are the caches most communicated about, or where a discussion around the ‘treasure’ has emerged, this way demonstrating the degree to which a community is engaged in or formed around a cache. For most Geocachers the journey and the narrative around the Geocache seems to be of a similar, or even bigger, importance than finding the treasure.

Fig 5 – Geocachers logged visits and most discussed caches. This map forms part of the Digital Methods Summer School at the University of Amsterdam in June 2014 (Credits: Joe Shaw – participant of the summer school)

Fig 5 – Geocachers logged visits and most discussed caches. This map forms part of the Digital Methods Summer School at the University of Amsterdam in June 2014 (Credits: Joe Shaw – participant of the summer school)

Geocaching is a phenomenon that enables discovering (re)new(ed) ways of experiencing the city. Geocache communities hold strong ties with physical locations, which are sustained by the digital exchange amongst the community members. A designer that embarks on working with such a community needs to understand the importance of engaging in both the physical and the virtual dimension, in order to generate a sustained intervention. Geocachers approach this dual engagement by creating a narrative around a cache and by directing the navigation on this narrative. In order to engage this community, a designer could either choose to build upon an existing narrative, or he/she could create an entirely new narrative by using a similar tactic. Furthermore, due to the nature of Geocaching, where users are keen on discovering new places, the designer is not restricted to designing interventions for known locations within the Geocaching community (i.e. the spots where the Geocaches are already placed), instead new places can be introduced and activated in playful ways, while respecting the navigational practice that is based on a narrative.

Discovering communities through language and time spans

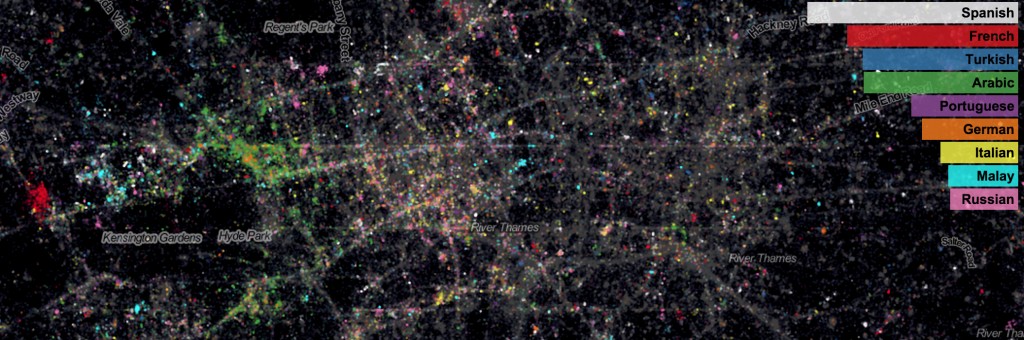

Other examples of digital methods that are utilised to demonstrate (virtual) communities and their respective use of different locations in the city (and of physical public spaces) can be found in Eric Fischer’s studies Geotaggers’ World Atlas (fig. 6) and Twitter Tongues (fig. 7). The first study maps traces of geotagged photos in fifty different cities from the platforms Flickr and Picasa, documenting the city from either the locals’ or the tourists’ perspective. The second study, Twitter Tongues, visualises the multilingual social city of London by highlighting areas where different languages are spoken in the city. In the map coloured clusters emerge, demonstrating dominant language use in different areas. However, what this second map doesn’t differentiate in are locals’ versus visitors’ tweets. In Geotaggers’ World Atlas the distinction between tourists and locals is made by the speed at which the photographers travelled (by analysing the timestamps and geotags of the photos). The blue dots on the map represent locals (users taking pictures in the same city for over a month), the red dots represent tourists (users taking pictures for a period that is less than one month) and the yellow ones remain uncategorised.

Fig 6 – Fischer’s map: Geotaggers’ World Atlas (left) (flickr.com)

Fig 6 – Fischer’s map: Geotaggers’ World Atlas (left) (flickr.com)

Fig 7 – Fischer’s map: Twitter Tongues (right) (twitter.mappinglondon.co.uk)

These kinds of social data can be valuable for designers in order to better understand the cultural background of a place where an intervention is planned, or to attract a certain cultural community for an intervention; in that case the findings can inform designers on where to best place a design intervention. Combining the analytical approaches of the two maps could embark an exploration into local cultures or multi-cultures in a certain area. These findings can inform designers to develop projects that consider the cultural dimension in the area. With this the designer can work with and/or focus on one established community or cultural group, therewith allowing the appropriation of the design intervention by a specific local community.

In Eizenberg’s work (2011) this cultural perspective on a neighbourhood scale is experienced as successful in terms of long-term appropriation and community engagement in public space. In her study on community gardens in New York City she learned that, due to ethnically segregated neighbourhoods and building blocks, many of the gardens existed of mono-ethnic spaces. This cultural clustering allowed for a spatial expression of these specific cultures, increasing the appeal of use and appropriation of the space by that specific cultural community. Since most of the gardeners in Eizenberg’s research were immigrants, the gardens were used as spaces for symbolic re-enactment of their childhood landscapes. The gardens allowed them to identify with the space while in turn, giving these local communities the chance to develop a sense of ownership and control over the gardens. This way the community gardens received a symbolic role as carriers of, and windows to, different cultures within the city. This example of diverse cultural use and its implications on appropriation of public spaces, illustrates possible applications for studies such as Fischer’s language map in design interventions.

These examples show that location based social data on communities (e.g. virtually constructed communities and/or communities with a similar cultural background) can help inform designers on the approach and location for their intervention, with the aim of enabling appropriation of the design intervention by these communities, thereby safeguarding its sustainability. The following section will introduce the second approach (i.e. from location to community), by presenting two new examples.

[FROM LOCATION TO COMMUNITY]

Mining location specific data

For the renewal of the old energy plant ‘Strijp-S’ in Eindhoven, architecture and research office Space and Matter were invited to conduct a conceptual study on the transformation of some spaces of the building. Prior to developing a design, the office investigated the current users of these spaces and its immediate surroundings. In this way, they aimed at developing a design proposal that could be appreciated and appropriated by the existing users. In order to find the current users, the office mined location specific data from social media platforms. The benefit of mining this data (over visiting the location) is the possibility to gain insight on the location’s use and appropriation at different times of the day and over a longer period of time (weeks, months, years). From this analysis they found that there were two existing communities: a group of skaters and BMX bikers, and a group of climbers (De Waal and De Lange, 2013). Following these findings, the office contacted and interviewed these communities in order to discover their specific programmatic and spatial needs. With this input, the office designed a conceptual plan for a hybrid space (spaceandmatter.nl) that both communities could use.

Although the firm’s design was never implemented, with the help of the municipality of Eindhoven the two communities were allowed to take over spaces in the old energy plant; in 2008 the climbing facility ‘Monk Boulder Gym’ was established here, and in 2010 ‘040 BMX Park’ moved into the building (monkeindhoven.nl; 040bmxpark.nl). Especially the relocation of the skate and BMX communities has triggered a larger community of hip-hop artists to establish their studios in this building. Break-dancers, rappers, and others were attracted by the location, which is now transforming into a larger entity (offering thirty workplaces) that’s being increasingly appropriated by related communities of artists and sub-cultures within the local hip-hop scene (Eindhovens Dagblad, 2014)

Mining Location Based Social Networks (LBSNs) Data

As mentioned previously, the examples of design practice working with digital methods that succeed in sustaining community participation are scarce. Furthermore, examples of design projects that do, and start out from a location to discover communities, are even more rare. The meagre results in this field can be explained by the novelty of working with digital social data, which means that there is still a lot to be explored in terms of their possibilities for the design profession. Therefore, instead of being restricted by art and design fields, we look at the field of marketing, which has been leading in exploring new uses and approaches for Big Data analysis as it has proven to be exceedingly successful for many businesses (such as Amazon, Google, Facebook, and so on). We believe that a lot can be learned from these marketing approaches in regards to the design profession exploring sustained civic engagement. This section will elaborate on one of these approaches and draw lessons from it.

Over the last years, there has been a growth in geo-located social network data, through platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Foursquare, etc. These location-based social networking tools allow users to “check in” at physical locations and share their whereabouts with their online contacts (Gao & Lui, 2014). With this, online social networks are increasingly using location-based services to assist in physical social encounters and in the discovery of new places in the city. Some architectural and urban design researchers use the data of such networks to uncover, and gain insight in, the distribution and spatial patterns of social life in a city (Bawa-Cavia, 2011). In marketing and computer science studies, a different approach towards this data has been developed. Here, location-based social network data from sources such as Foursquare or Facebook Places, are analysed in order to discover user communities (Cranshaw et al, 2010; Hung et al, 2009; Ying et al, 2010). By estimating the similarity of location histories of two different users, the likelihood of these users belonging to a community is explored. This similarity represents the strength of a possible connection between the users. In this way, location-based social networking services can apply the user-similarity findings to optimise their friend recommendation or location recommendation features. Such services can for instance discover locations based on similar users that are compatible with the user’s preferences, and with that develop a ‘personalised location recommender system’ (Zheng, 2011, p.262). While most research from a marketing perspective is aimed at finding new ways to improve such recommendation features (Wang et al, 2014; Zheng, 2011), we’re interested in whether this algorithm-driven method of community discovery could be a useful tool for designers in our proposed approach. This paper will not step into detail about the specific technological advances and computational specificities of discovering such communities. Instead we focus on what these studies qualify as a community in the data analysis, and question whether this could be a potential method for designers to discover communities in the locations they plan to intervene in, prior to developing a design intervention.

As mentioned in the hypothesis, we argue that there are two aspects that are important in the ability to sustain a design intervention: acknowledging existing communities and understanding the community’s interests. The LBSNs research projects address these two aspects in the following way: the common belief is that people who share similar location histories in these applications are likely to have similar interests and preferences. This idea is based on Tobler’s first law of geography: ‘Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things’ (Tobler, 1970, p.236). But not only the geographic space is analysed, the semantic space is an important factor that is taken into consideration as well. These researchers share a belief that a person who often visits stadiums and gyms is likely to be fond of sports. Therefore, another claim is articulated: people that access locations with similar semantic meanings (e.g. the cinema) have a greater likelihood of being similar, and therefore are more likely to belong to one or more of the same communities.

The LBSNs research approaches indicate that communities are not only shaped by shared geographic locations, but also by shared semantic meanings of places. This notion is reflected in Eizenberg’s (2011) example, where a shared (cultural) semantic allowed cultural communities to collectively experience and appropriate the local public space. Therefore, we argue that understanding the use and semantic meaning of the shared spaces can help designers to define a fitting program and approach for an intervention. This thinking is in line with the previously introduced example in Eindhoven, where a community of skaters and BMX-bikers, and a community of climbers formed the main influence of the design of the space. As a result of the programming of these spaces, the communities were able to appropriate the space, and with that, sustained the use of and participation in the space.

[Conclusion]

Instead of proposing a specific method for designers to achieve sustained civic engagement, this paper aims to provide the reader with clues, emerging from existing examples from a broad field, as directions for further explorations to discover the value of digital methods for the design profession.

The first clue comprises the mapping of virtual communities’ use of public places, enabling a designer to understand the appropriation and meaning of a place (such as a square, a bar or a certain neighbourhood) to a community. The Location Based Social Networks (LSBNs) example introduced some technological advances around the use of geo-social data. Data from platforms such as Twitter, Foursquare and Facebook are explored, for marketing purposes that is, in order to discover user communities. The LSBNs research projects aim at uncovering communities from single users data, not only through the locations they visit, but also through the semantic meanings of these locations. In the research on the platforms Pinterest, Meetup and Geocaching, location’s semantics also emerged as an important factor in the shared experience of a community. It illustrates that space is not only appropriated but also simultaneously, and continuously, made by a community through the narrative and meaning that is collectively given to it. Especially in Geocaching, the virtual layer shapes the physical domain, and the physical domain strengthens or forms communities (in this case the location where a cache is placed or the route towards it). Therefore, if designers want to be informed by these virtual platforms on where to design an intervention, with what program and for whom, they need to be aware of how to engage in the community’s virtual realm. This virtual dimension allows designers to either learn from the community’s created meaning of a place or actively engage in the creation of meaning of a place that is in the interest of the specific community. The study of the different virtual platforms also showed that not all platforms are necessarily useful for designers to explore practices of communities’ appropriation of places (Pinterest for example is more about consumerism than about civic engagement in physical places).

The second clue is introduced by Fischer’s maps, which highlight places in the city that are appropriated by different communities (locals, tourists and bilinguals). This study can form a starting point for designers to investigate where communities with different cultural backgrounds are located within the city. This way, a designer can plan an intervention around a specific community, allowing the community to articulate their specific use of the space. The single-ethnic gardens in New York illustrated that these unique uses shaped by a community’s culture allow for different experiences of the space through its spatial arrangement, aesthetic expression, and specific use (influenced by culinary preferences, customs, rituals and so on). Through this cultural clustering, gardeners are able to experience, celebrate and express their culture in a collective way, which allows them to contextualise their sense of attachment and belonging to the collective culture, as well as their immediate environment. Enabling on-going production and participation in the gardens allows community members to grow a sense of ownership, which leads to sustained engagement of communities in these cultural spaces.

The Eindhoven example offers a third clue. It demonstrates that places appropriated by specific communities can also attract other, related communities, and with that transform an area into a cultural cluster. This, in turn, increases the resilience of a space in terms of sustained engagement. When one of the communities loses its interest or motivation to engage with the space, other communities can take over or can use the space in a more hybrid way, making the space more resilient when user patterns transform.

The examples in this paper have introduced different possible approaches for designers to explore virtual communities or geo-social data to engage with citizens that can sustain the design interventions. We believe that, as the technology advances, the possibilities for designers to explore different digital approaches increase as well. Throughout this paper we have introduced a variety of examples of contemporary approaches, however, we believe that there is still a wide field of yet to be discovered possibilities. These possibilities, or rather opportunities, should trigger and inspire designers and design researchers to explore social data and digital methods as approaches to developing sustained participation in public space design interventions.

References

596 Acres 2011-2012 Recap. 2012. Available from: http://596acres.org/media/filer_public/2012/12/29/596_acres_2011-2012_recap.pdf [Accessed: 17/10/ 2014].

Bawa-Cavia, A. 2011. Sensing the Urban: Using Location-Based Social Network Data in Urban Analysis. Pervasive PURBA Workshop.

Cranshaw, J., Toch, E., Hong, J., Kittur, A. & Sadeh, N. Bridging the Gap Between Physical Location and Online Social Networks. 12th ACM International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing (Ubicomp), 2010 New York. ACM, pp. 119-128.

De Lange, M. & De Waal, M. 2013. Owning the City: New Media and Citizen Engagement in Urban Design. 18. [Accessed 08/02/2015].

Eindhovens Dagblad. 2014. Hiphop cluster krijgt vorm op Strijp-S. [online] Available from: http://www.ed.nl/regio/eindhoven/hiphopcluster-krijgt-vorm-op-strijp-s-1.4286862 [Accessed 26/03/2014].

Digital Methods Summer School maps. 2014. Availabe from: https://wiki.digitalmethods.net/Dmi/SummerSchool2014 [Accessed 24/04/2015].

Eizenberg, E. 2011. Actually Existing Commons: Three Moments of Space of Community Gardens in New York City. Antipode, 44, pp. 764-782.

Gao, H. & Liu, H. 2014. Data Analysis on Location-Based Social Networks. In: Chin, A. & Zhang, D. (eds.) Mobile Social Networking: An Innovative Approach. Springer.

Hung, C. C., Chang, C. W. & Peng, W. C. Mining Trajectory Profiles for Discovering User Communities. International Workshop on Location Based Social Networks, 2009 New York. ACM, pp. 1-8.

Lane, G. et al. 2006. Public Authoring & Feral Robotics. In: Proboscis. Cultural Snapshot Number Eleven. Available at: http://proboscis.org.uk/publications/SNAPSHOTS_feralrobots.pdf [Accessed: 8 Nov 2014].

Segal, P. 2014. OpenGov Voices: How 596 Acres is opening up vacant lots data. Sunlight Foundation [web log]. Available at: http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2014/07/03/opengov-voices-how-596-acres-is-opening-up-vacant-lots-data/ [Accessed: 13 Nov 2014].

Tobler, W. R. 1970. A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region. Economic Geography, pp. 234-240.

Wang, Z., Zhang, D., Zhou, X., Yang, D., Yu, Z. & Yu, Z. 2014. Discovering and Profiling Overlapping Communities in Location-Based Social Networks. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, 44, pp. 499-509.

Ying, J. J. C., Lu, E. H. C., Weng, T. C. & Tseng, V. S. Mining User Similarity from Semantic Trajectories. 2nd ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Location Based Social Networks, 2010 New York. ACM, pp. 19-26.

Zheng, Y. 2011. Location-Based Social Networks: Users. In: Zheng, Y. & Zhou, X. (eds.) Computing with Spatial Trajectories. Springer.